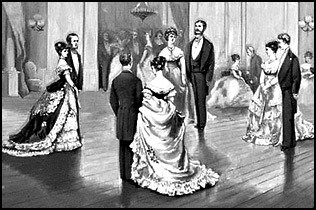

"I danced the quadrille with all the bearing I needed and could muster. I cannot hide the fact that at that time of misery finding me in touch and hand-in-hand with the future Queen of Italy gave me great satisfaction."

The death of a beloved mother and much-admired older brother had fallen as particularly heavy blows upon Tommaso Juglaris. Then Juglaris’s father, Carlo Maria, became gravely ill. Although there had been a falling-out between father and son over the latter’s choice of an artistic vocation, Juglaris did everything possible to ensure that his father had the best available medical care, spending all he earned. However, despite every attempted cure, the elder Juglaris continued to waste away. Finally, towards the end of 1869, Carlo Maria Juglaris died, right in his son’s arms.

In his father’s last days, Tommaso Juglaris was consoled by a deathbed benediction with Carlo Maria "nearly begging…pardon for having so opposed [his son’s] career." Unfortunately, the elder Juglaris also left behind 2,000 lire in family debts and a younger brother enrolled in a state military school who needed support. Concerned about the reputation of his family name in Moncalieri and Turin, Juglaris felt obliged to assume his father’s debts and his brother’s care. It would take more than a decade for all the debts to be repaid.

Despite such profound and haunting losses, Juglaris did enjoy some lighter, happier moments in his young life. He loved to dance. In his memoir Juglaris describes a particularly memorable evening at the elegant Ballo Grande del Circolo which he attended in a newly-purchased black suit, top hat, and gloves. Hosted by the Artists’ Circle of Turin at the Palazzo Graneri della Roccia, the event was the “most aristocratic dance held at that time” in the city. Along with all the local nobility, the entire royal court gathered for the occasion. To Juglaris’s immense delight he was invited to share a dance with an Italian princess—the future Queen Margherita of Italy. “I remember,” Juglaris notes, “that in a quadrille, Count Marcello di Panissera, having asked the organizers [of the ball], introduced me to his wife, begging me to take his place. In that group of eight couples was the Princess Margherita… I was to be her vis-à-vis [i.e., partner]. I danced the quadrille with all the bearing I needed and could muster. I cannot hide the fact that at that time of misery finding me in touch and hand-in-hand with the future Queen of Italy gave me great satisfaction. I even forgot that on the morrow I had nothing to eat. Oh illusion!” It was an ecstatic, Cinderella-like moment for Juglaris.

Juglaris’s enjoyment of Turin’s high society threw his struggle with everyday life into even sharper relief. Without a family to fall back on or the financial means to be selective about the work he accepted, he was perennially vulnerable to exploitation by better-known artists who hired him as an assistant or subcontractor. He rightly felt that others were taking advantage of him, claiming credit for his work and cheating him of pay.