"I was no longer in practice with the brush, since I had been doing industrial art for some time...Art in Paris is too beautiful and were I to attempt it I would be a failure, and so I have dedicated myself to industrial art and am pleased with it."

At the time of his arrival in Paris in 1870, Juglaris was already a 26 year-old man—too old to enroll for regular study at the city’s fabled Ecole des Beaux Arts as he might have preferred. Grateful for the money that he was able to earn through industrial art to comfortably support himself in Paris, Juglaris did not immediately fret about lost or impaired opportunity. Meanwhile, with every passing day, it also seemed less likely that he could ever change course from industrial to fine arts. As Juglaris frankly summed up his situation in his memoirs: “I was no longer in practice with the brush, since I had been doing industrial art for some time.” Yet behind all this was a nagging lack of confidence in his own abilities, particularly in comparison to the talents of others in his adopted city. “Art in Paris,” Juglaris actually rationalized, “is too beautiful and were I to attempt it I would be a failure, and so I have dedicated myself to industrial art and am pleased with it.”

All this began to change as Juglaris gradually became more honest with himself and clearer about his responsibility to his vocation. Juglaris came to realize and accept that, whatever the odds against him, including the difficulty of finding the necessary time to do more, he could never rest satisfied with a career strictly focused on industrial art. First of all, he had come to Paris to learn. Secondly, he wanted the reputation and stature that could only be achieved by making a mark in the fine arts and mural work, alongside his success with industrial art.

Although the doors of the Ecole des Beaux Arts had appeared firmly closed to him, Juglaris learned that two of the most famous academic painters of the day from the school’s faculty, namely, Jean-Leon Gerome and Alexandre Cabanel, were willing to take him on as an external student through night classes. Accordingly, much as he had at Turin’s Accademia Albertina, Juglaris pursued after-hour art studies with these great French masters. Both men profoundly shaped Juglaris’s outlook and style as an artist.

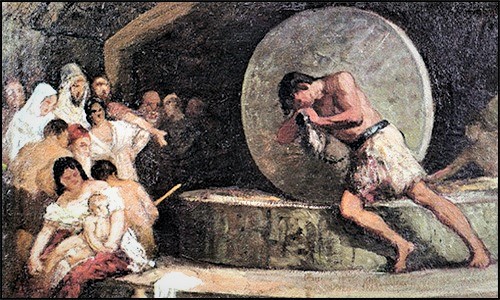

Circulating widely in Parisian art circles over the next couple of years, Juglaris also eventually met and benefited from the advice of such other distinguished artists as Camille Corot, Leon-Joseph-Florentin Bonnat, and Thomas Couture. Indeed, as need arose, he freely consulted them with regard to paintings underway on his own studio easel. Among works in progress that prompted him to solicit such advice was a large, biblically-inspired canvas (Judges 16:21), presenting a blinded and imprisoned Samson shackled to a grindstone by the Philistines, which may have had personal resonance for Juglaris trying to break free from the shackles of industrial art.